Background

Sometimes a rather obscure and complex analogy just clicks into place in one’s mind and allows a slightly altered way of thinking that just makes so much sense it hurts. Like putting glasses on in the morning and the world suddenly snapping into shape.

This happened to me this morning when reading the Notes from Two Scientific Psychologists blog and the post Do people really not know what running looks like?

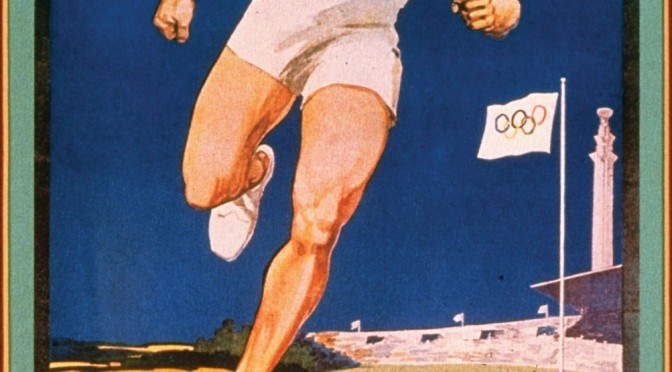

It describes the fact that many famous painters (and authors of instructional materials on drawing) did not depict running people correctly. When running, it is natural (and essential) to put forward the arm opposite the leg that’s going forward. But many painters who depict running (including the artist who created the poster for the 1922 Olympics!) do it the wrong way round. Not just the wrong way, the way that is almost impossible to perform. And this has apparently been going on for as long depiction has been a thing. But it’s not just artists (who could even argue that they have other concerns). What’s more when you ask a modern human being to imitate somebody running by assuming a stationary pose (as somebody did on the website Phoons) they will almost invariably do it the wrong way round. Why? There are really two separate questions here.

- Why don’t the incorrect depictions of running strike most people as odd?

- Why don’t we naturally arrange our bodies into the correct stance when asked to imitate running while standing still?

Andrew Wilson (one of the two psychologists) has the perfect answer to question 2:

Asking people to pose as if running is actually asking them to stand on one leg in place, and from their point of view these are two very different things with, potentially, two different solutions. [my emphasis]

And he prefaces that with a crucial point about human behavior:

people’s behaviour is shaped by the demands of the task they are actually solving, and that might not be the task you asked them to do.

Do try this at home, try to imitate a runner standing up, then slowly (mime-like), then speed it up. Standing into the wrong configuration is the natural thing to do. Doing it the ‘right’ way round, is hard. It’s not until I sped up into an actual run that my arms found the opposite motion natural until I couldn’t keep track of what was going on any more. I would imagine that this would be the case for most people. In fact, the few pictures I could find of runners arranged standing at the start of the race have most of them also with the ‘wrong’ hand/leg position and they’re not even standing on one leg. (See here and here.)

Which brings us back to the first question. Why does not anybody notice? I personally find it really hard to even identify the wrong static description at a glance. I have to slow down, remember what is correct, then match it to the image. What’s going on? We obviously don’t have any cognitive control over the part of running that controls the movement ofarms in relation to the movement of legs. We also don’t have any models or social scripts that pay attention to this sort of thing. It is a matter of conscious effort, a learned behaviour, to recognize these things.

Why is this relevant to language?

If you ask someone to describe a language, they will most likely start telling you about the words and the rules for putting them together. In other words, compiling a dictionary and a grammar. They will say something like: “In Albanian, the word for ‘bread’ is ‘bukë'”. Or they will say something like “English has 1 million words.”, “Czech has no word for training.” or “English has no cases.”

All of these statements reflect a notion of language that has a list of words that looks a little like this:

bread n. = 1. baked good, used for food, 2. metaphor for money, etc.

eat v. = 1. process of ingestion and digestion, 2. metaphor, etc.

people n. plural = human beings

And a grammar that looks a little bit like this.

Sentence = Noun (subj.) + Verb + Noun (obj.)

All of this put together will give us a sentence like:

People eat food.

All you need is a long enough list of words and enough (but not as many) rules and you got a language.

But as linguists have discovered through not a bit of pain, you don’t have a language. You have something that looks like a language but not something that you can actually speak as a language. It’s very similar to language but it’s not language.

Kind of like the picture of the runner with the arms going in the opposite direction. It looks very much like someone running but it’s not, it’s just a picture of them imitating running and the picture is fundamentally mismatched with the stated aim. Just not in a way that is at all obvious to most people most of the time.

Why grammars and dictionaries seem like a good portrait of language

So, we can ask the same two questions again.

- Why does the stilted representation of language as rules and words not strike most people (incl. Steven Pinker) as odd?

- Why don’t we give more realistic examples of language when asked to imitate one?

Let’s start with question 2 again which will also give us a hint as to how to answer question 1.

So why, when asked to give an example of English, am I more likely to come up with:

John loves Mary.

or

Hello. Thank you. Good bye.

than

Is it cold in here? Could you pass the sugar, please. No no no. I’ll think about it?

It’s because I’m achieving a task that is different from actually speaking the language. When asked to illustrate a language, we’re not communicating anything in the language. So our very posture towards the language changes. We start thinking in equivalencies and left and right sides of the word (word = definition) and building blocks of a sentence. Depending on who we’re speaking to, we’ll choose something very concrete or something immediately useful. We will not think of nuance, speech acts, puns or presupposition.

But the vast majority of our language actions are of the second kind. And many of the examples we give of language are actually good for only one thing: Giving an example of the language. (Such as the famous example from classical logic illustrating a proposition ‘A man walks’ which James MacCawley analysed as only being usable in one very remote sense.)

As a result, if we’re given the task of describing language, coming up with something looking like a dictionary and a grammar is the simplest and best way of fullfilling the assignment. If we take a scholarly approach to this task over generations, we end up with something that very much looks like the modern grammars and dictionaries we all know .

The problem is that these don’t really give us “a picture of language”, they give us “a picture of a pose of language” that looks so much like language to our daily perception, that we can’t tell the difference. But in fact, they are exactly the opposite of what language looks like in motion.

Now, we’re in much more complex waters than running. Although, I imagine the exact performance of running is in many ways culturally determined, the amount of variation is going to be limited by the very physical nature of the relatively simple task. Language on the other hand, is almost all culture. So, I would expect people in different contexts to give different examples. I read somewhere (can’t track down the reference now) that Indian grammarians tended to give examples of sentences in the imperative. Early Greeks (like Plato) had a much more impoverished view of the sentence than I showed above. And I’m sure there are languages with even more limited metalanguage. However, the general point still stands. The way we tend to think about language is determined by the nature of the task

The key point I’ve repeated over and over (following Michael Hoey) is that grammars and dictionaries are above all texts written in the language. They don’t stand apart from it. They have their own rules, conventions and inventories of expression. And they are susceptible to the politics and prejudices of their time. Even the OUP. At the same time, they can be very useful tools to developing language skills or dealing with unfamiliar texts. But so does asking a friend or figuring out the meaning in context.

Which brings us to question 1. Why has nobody noticed that language doesn’t quite move the way we paint it? The answer is that – just like with running – people have. But only when they try to match the description with something that is right in front of them. Even then, they frequently (and I’m talking about professional linguists like Stephen Pinker here) ignore the discrepancy or ascribe it to a lack of refinement of the descriptions. But most of the time, the tasks that we fulfil with language do not require us to engage the sort of metacognitive aparatus that would direct us to reflect on what’s actually going on.

What does language really look like

So is there a way to have an accurate picture of language? Yes. In fact, we already have it. It’s all of it. We don’t perhaps have all the fine details, but we have enough to see what’s going on – if we look carefully. It’s not like linguists of all stripes have not described pretty much everything that goes on with language in one way or another. The problem is that they try to equate the value of a description to the value of the corresponding model that very often looks like an algorithm amenable to being implemented in a computer program. So, if I describe a phenomenon of language as a linguist, my tendency is to immediately come up with a fancy looking notation that will look like ‘science’. If I can make it ‘mathematical’, all the better. But all of these things are only models. They are ways of achieving a very particular task. Which is to – in one way or another – model language for a particular purpose. Development of AI, writing of pedagogic grammars, compiling word lists, predicting future trends, tracing historical developments, estimating psychological impact, etc. All of these are distinct from actual pure observation of what is going on. Of course, even simple description of what I observe is a task of its own with its own requirements. I have to choose what I notice and decide what I report on. It’s a model of a sort, just like an accurate painting of a runner in motion is just a model (choosing what to emphasize, shadows, background detail, facial expression, etc.) But it’s the task we’re really after: Coming up with as accurate and complete a picture of language as is possible for a collectivity of humans.

People working in construction grammars in the usage-based approach are closest to the task. But they need to talk with people who work on texts, as well, if they really want to start painting a fuller picture.

Language is signs on doors of public restrooms, dirty jokes on TV, mothers speaking to children, politicians making speeches, friends making small talk in the street, newscasters reading the headlines, books sold in bookshops, gestures, teaching ways of communication in the classroom, phone texts, theatre plays, songs, blogs, shopping lists, marketing slogans, etc.

Trying to reduce their portrait to words and rules is just like trying to describe a building by talking about bricks and mortar. They’re necessary and without them nothing would happen. But a building does not look like a collection of bricks and mortar. Nor does knowing how to put a brick to brick and glue them together help in getting a house built. At best, you’d get a knee-high wall. You need a whole of other knowledge and other kinds of strategies of building corners, windows, but also getting a planning permission, digging a foundation, hiring help, etc. All of those are also involved in the edifices we construct with language.

An easy counterargument here would be: That’s all well and good but the job of linguistics is to study the bricks and the mortar and we’ll leave the rest to other disciplines like rhetoric or literature. At least, that’s been Chomsky’s position. But the problem is that even the words and grammar rules don’t actually look like what we think they do. For a start, they’re not arranged in any of the ways in which we’re used to seeing them. But they probably don’t even have the sorts of shapes we think of them in. How do I decide whether I say, “I’m standing in front of the Cathedral” or “The Cathedral is behind me.”? Each of these triggers a very different situation and perspective on exactly the same configuration of reality. And figuring out which is which requires a lot more than just the knowledge of how the sentence is put together. How about novel uses of words that are instantly recognizable like “I sneezed the napkin off the table.” What exactly are all the words and what rules are involved?

Example after example shows us that language does not look very much like that traditional picture we have drawn of it. More and more linguists are looking at language with freshly open eyes but I worry that they may get off task when they’re asked to make a picture what they see.

Where does the metaphor break

Ok, like all metaphors and analogies, even this one must come to an end. The power of a metaphor is not just finding where it fits but also pointing out its limits.

The obvious breaking point here is the level of complexity. Obviously, there’s only one very discretely delineated aspect of what the runners are doing that does not match what’s in the picture. The position of the arms. With language, we’re dealing with many subtle continua.

Also, the notion of the task is taken from a very specific branch of cognitive psychology and it may be inappropriate extending it to areas where tasks take a long time, are collaborative and include a lot of deliberately chosen components as well as automaticity.

But I find it a very powerful metaphor nevertheless. It is not an easy one to explain because both fields are unfamiliar. But I think it’s worth taking the time with it if it opens the eyes of just one more person trying to make a picture of language looks like.